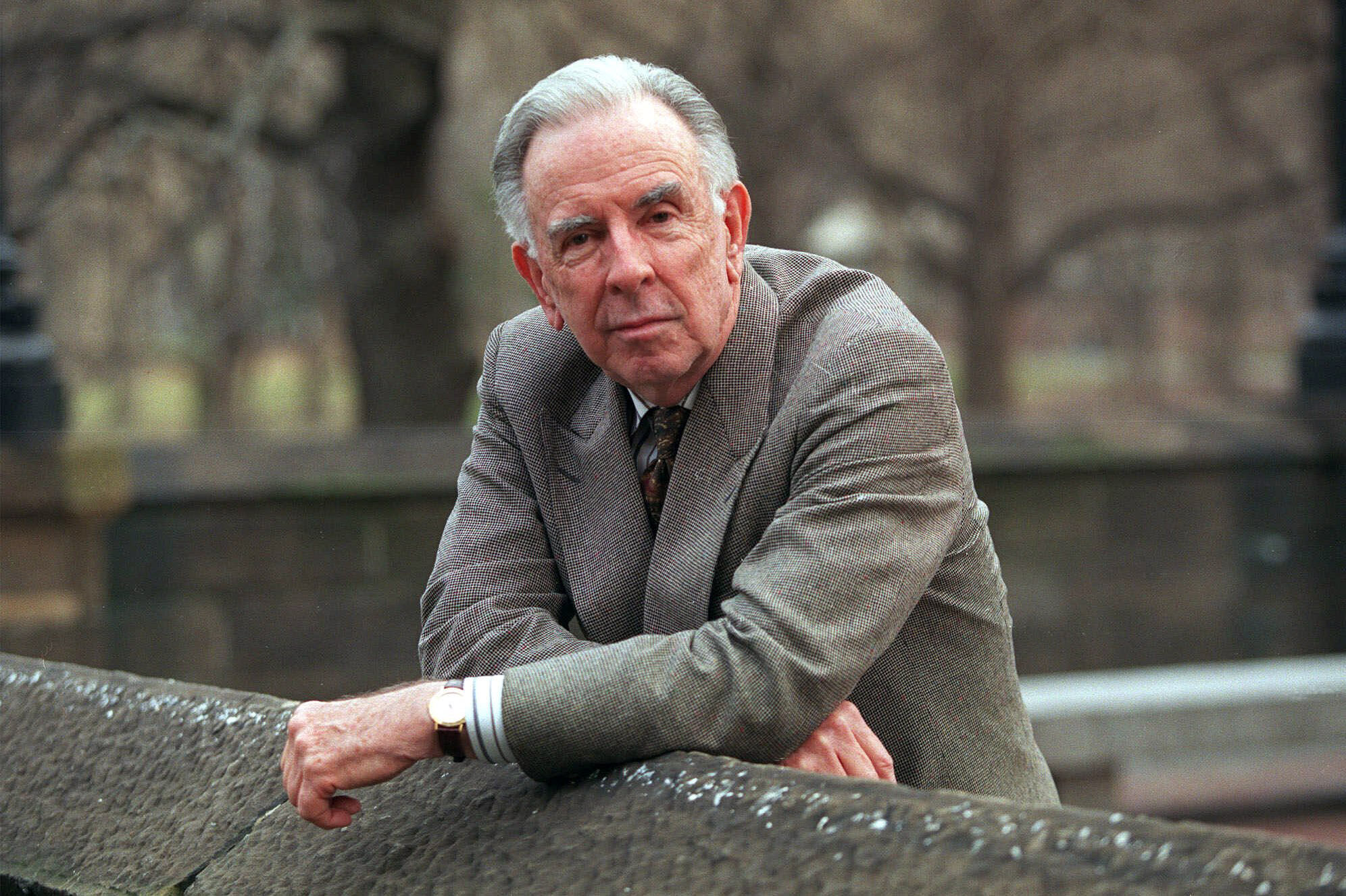

Carlisle Floyd: Composer, Mentor, Visionary

As we approach Carlisle Floyd’s 2026 birth centennial, it is mandatory to honor him for the creation of thirteen such groundbreaking operas as Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Cold Sassy Tree, and his last, Prince of Players; yet it further behooves us to recognize that his life and career encompassed the work of at least five men: librettist, composer, educator, administrator, and spokesperson for his craft and its sponsoring institutions. A half-century of teaching at Florida State University (1949-1975) and University of Houston (1975-1996) informed generations of singers, conductors, coaches, and composers; and into his nineties he offered private mentoring to such twentieth- and twenty-first century talents as Mark Adamo, Matthew Aucoin, Jake Heggie, Henry Mollicone, and Rufus Wainwright.

Carlisle established a serious presence early, with a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1956, and a Ford Foundation grant in 1959. Over succeeding decades, he won most of the awards and distinctions available to creative artists, including membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters (2001), a National Medal of Arts, presented by President George W. Bush in 2004; and the National Endowment for the Arts Opera Honors (2008).

His involvement with the Kennedy Center and its allied National Opera Institute (NOI) since the 1970s made him instrumental in commissioning new operas; financing training, coaching, and living expenses for operatic artists; and securing funding for touring performances of operas in far-flung areas of our country. His appointment to a ten-year term on the organization’s artists’ awards committee brought his humanizing presence to award ceremonies and social events.

Carlisle’s long association with Houston Grand Opera (HGO) led to co-founding with its general director David Gockley the Houston Opera Studio, which provided advanced training and career development for young artists chosen for their potential to make noteworthy contributions to opera and musical theater.

When the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) instituted its Opera-Musical Theater program (OMT), Carlisle became its first chairman, with new duties that included guiding panel meetings, coordinating business affairs, evaluating productions, and representing the NEA with regional opera boards. Owing to his diplomatic skills and OMT’s interdisciplinary nature, effective cooperation flourished between its constituent parts. Thanks to his ongoing relationship with HGO, the company’s Studio became the site for production of OMT’s commissioned works.

This whirlwind of administrative duties became just another element of Carlisle’s occupation, and lest we lose sight of his undiminished creative drive, the years from his first FSU hire in 1955 to retirement in 1996 saw his creation of both words and music of Susannah (FSU, 1955), Wuthering Heights (Santa Fe, 1958 and New York City Opera, 1959), The Passion of Jonathan Wade (New York, 1962), The Sojourner and Mollie Sinclair (Raleigh, North Carolina, 1963), Markheim (New Orleans, 1966) Of Mice and Men (Seattle, 1970), Flower and Hawk (Jacksonville, 1972), Bilby’s Doll (Houston, 1976), Willie Stark (Houston, 1981); and the new incarnation of The Passion of Jonathan Wade (Houston, 1991).

Opera America, embracing most of our professional and semi-professional companies, was founded in Seattle in 1970, an occasion also marked by Of Mice and Men’s world premiere. Carlisle was intrigued by the organization’s goal of inter-company cooperation, but initially skeptical of what he feared might prove “an old boys club.” Yet his prominence in its ranks and his commitment to all forms and venues of music theater overcame such concerns and made him a natural spokesperson for Opera America’s ethos. His advocacy for resourceful new companies, improved quality of productions, second and third hearings for new works, and the innovation of supertitles prompted general rejoicing and growth; and his abiding missions continued: resisting predictability of the familiar, tired repertoire warhorses that exerted the “tyranny of the box office;” “deconstructive,” as opposed to “innovative” directorial conceits; and the lack of effective arts education.

Another of Carlisle’s most telling preoccupations was the relationship of artist and audience. His remarks, “Summing Up at Seventy,” for Opera America’s Newsline continue speaking to twenty-first-century concerns: “What redeems artists from the charge of arrogance…is a constant awareness that, while it is the artist’s unquestioned function to lead…it is imperative that he at all times look over his shoulder to be certain that there is someone following…We—the creators of opera and the opera audience—have to find a common language…and I am afraid the responsibility is more on our side than on the audience’s…I continue to marvel at the unique expressive power of this art form. The world of opera is the world of the large gesture, the thrilling overstatement…rendered authentically human and emotionally convincing by passionately committed performers, the kind of artistic experience that results is unmatched anywhere else.”

-Thomas Holliday, February 2025

Photo Credit: SUZANNE PLUNKETT/Associated Press